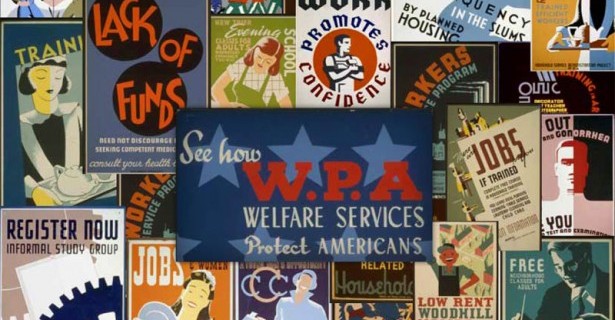

What an unabashed U.S. welfare state looked like, in the first half of the 20th century.

The Welfare State of America

A manifesto on building social democracy in the age of austerity.

October 22, 2012

We can’t go back to

the post-war golden age of the American welfare state, but we can build

a system in the 21st century that embodies what people remember most

from that era—an overriding sense of freedom.

Seething with contempt for half of America, Romney is a caricature of an out-of-touch elite.

He’s also, in a twisted way, right.

A movement to expand the welfare state has the potential to foster a new majoritarian Left coalition. Republicans know this—that’s why they manipulate the way welfare is perceived at every turn.

The reality is that 96 percent of Americans have benefited from government programs, but the Right works hard to hide that fact. It’s part of a deliberate strategy to divide the country into two camps by convincing the majority of voters that their labor is benefiting parasites dependent on the social safety net.

Democrats have too often bolstered this effort by echoing calls for “welfare reform” and “fiscal responsibility,” and by supporting policies that channel benefits through the tax code (such as the home-mortgage deduction) and private organizations (such as employer-provided health insurance). The result is a system that provides few benefits, makes them largely invisible and disproportionately benefits the more affluent.

In the face of this neoliberal consensus, the Left’s counter-mission must be to show that social democracy benefits everyone. Though this has been the errand of generations of liberals, their efforts have rarely gone beyond rebranding and messaging. Few have pushed for the structural changes necessary to build a strong welfare state.

One nation, underfunded

You get what you pay for, and we haven’t paid for much.

Compared to other rich countries, the United States does little to ensure its citizens have access to vital services or to prevent them from falling into deprivation due to unemployment or low-wage labor. At 19.4 percent of GDP, American social spending is far below the 25 to 30 percent budgeted in most of Western Europe. Meanwhile, 16 percent of Americans lack health insurance, almost a quarter of our children live in poverty, and millions are unemployed.

Yet not only does an expansion of the safety net seem politically impossible, even existing protections are under attack everywhere.

This might seem like a poor moment to call for expanding the welfare state. But the timing has never been better. Austerity has only worsened unemployment and stagnated wages, and only a concerted effort to employ idle workers and boost purchasing power can revive growth and restore employment. Despite fear-mongering about the effects of budget deficits, the government is still able to borrow money virtually interest-free. And contrary to right-wing claims of out-of-control spending, taxes as a percentage of GDP are at their lowest level since 1950. We can, and should, ensure that everyone has access to healthcare, education, a secure retirement and a livable income, regardless of labor market uncertainties.

Most on the Left would agree with these goals—the question has always been how to achieve them.

We think we have an answer. We propose a new anti-austerity coalition united by the immediate demand that certain social spending burdens, currently borne by states and municipalities, be federalized. Almost all states are legally required to keep balanced budgets, making it unfeasible for them to employ deficit spending to address to a cyclical economic downturn. Even if these laws were changed, states would still face far more difficulties in this arena than the federal government. States could never borrow money on as favorable terms as the United States can, and they haven’t been printing their own currencies since the Articles of Confederation.

Simply put, without centralization, true social democracy in America is impossible. Once achieved, progressives could pursue policies that not only immediately improve working-class lives, but also lay the groundwork for more radical reforms in the future.

The Cloward-Piven strategy

Radicals of another era also sought such change. In a 1966 Nation essay, “The Weight of the Poor: A Strategy to End Poverty,” Richard A. Cloward and Frances Fox Piven suggested a way to revolutionize how welfare was administered. Recognizing that few took ad- vantage of what they were entitled to by law, they proposed a campaign to educate the eligible about their rights. The resulting increase in claimants would cause a fiscal crisis for state and local governments, forcing the federal government to intervene.

Nationalizing the welfare system was, in Cloward and Piven’s words, a way to “wipe out poverty by establishing a guaranteed annual income.” Today, 46 years later, we find ourselves in a political environment far less favorable to the Left, with an even more tattered safety net. Yet the weight of the poor exerts less pressure on the American consciousness. The institutions of the Left are weak and fragmented, and the decline of the labor movement, long the linchpin of progressive organizing, has left the public sector as the last union stronghold. Rather than fighting to expand the welfare state, activists around the country are fighting to preserve the gains of the 20th century.

The Left needs an affirmative strategy that can go beyond the piecemeal defense of the status quo against austerity. The ambitious plan outlined by Cloward and Piven may seem like an artifact of another era, and it would have been all but forgotten if not for its resurrection by right-wing commentators like Glenn Beck. But Cloward and Piven’s ambition should inspire us to envision an equally comprehensive strategy that is adapted to the current state of our politics and economy, and that draws on existing areas of progressive strength.

For too long, liberals have focused on technocratic policy analysis, seeking granular remedies to isolated problems. Such solutions lack the kind of sweeping political vision that wins and sustains policy reforms. Conversely, radicals have for too long made rhetorical appeals without any grounding in political realities. The plan outlined below is a corrective to both trends, written with the understanding that policy and politics are inextricably linked.

How it can happen

Though the struggle over budget cuts has sparked debate at the national level, the politics of austerity has been even more prominent in the lower levels of government. The Great Recession severely constrained state and local revenues, and the resulting job cutbacks have in turn been a primary cause of the weak recovery.

Indeed, so long as social welfare programs are funded at the state and local level, the fiscal limitations of sub-national governments make austerity an unavoidable option.

Local movements may sporadically succeed at flanking the wave of cuts, but they will be fighting a losing battle as long as they are trying to win concessions from governments with little spending flexibility. In the long run, building a better and more robust social safety net will mean unifying and reorganizing our fragmented welfare state.

Some liberals defend the current system by holding up the states as “laboratories of democracy” that can pioneer new progressive initiatives that are impossible at a national level. Historically, however, the least progressive aspects of American welfare have been those that are passed off to the states, while the most generous and universal are national programs.

As the political scientist Suzanne Mettler observes in her book Dividing Citizens: Gender and Federalism in New Deal Public Policy, the elements of the New Deal that were left to the states were largely those that serve women and minorities, and these programs tend to subject recipients to surveillance and scrutiny by bureaucrats and social workers. National programs like Social Security and Medicare, which have a large proportion of white men on their rolls, are by contrast regarded as entitlements and their recipients treated with respect.

This pattern is likely to be perpetuated as long as large chunks of the safety net are administered by states, including the right-leaning states that are both hostile to welfare programs and contain a disproportionate share of the nation’s poor. It’s no coincidence that Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan’s budget plan pushes even more social welfare administration onto the states, by converting programs like Medicaid and food stamps into block grants.

Given the current disarray, a one-size-fits-all solution for consolidating the welfare state does not exist. Under a new progressive system, state and local spending could be transferred to federal programs in various ways.

• Welfare and unemployment: In these cases, where benefits are already a shared responsibility of federal and non-federal governments, Washington must simply assume more of the responsibility.

• Pensions: The current shortfall in pension funds is largely a result of the stock-market collapse after the burst of the housing bubble, and so this part of state and local budgets should improve as the economy improves.

Serious problems of underfunding remain in many places, however, and it is always tempting for politicians to plug present-day budget holes by shortchanging future pension obligations. Some type of federal bailout of these plans may be required if workers are to receive the benefits they are contractually entitled to, especially if there is another recession.

The federal government already has an entity, the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, responsible for ensuring that private-sector employees receive their pensions even when their plans fail or their employers go bankrupt. Something analogous may need to be created for employees of local and state governments. As a long-term solution, however, it makes little sense for state and local public-sector pensions to be on local budgets and subject to the fluctuations of the stock market. These workers should be fully brought into the Social Security system, like their private-sector and federal counterparts.

• Healthcare: Alleviating the burden of healthcare spending on the states will require addressing the irrationalities of the American healthcare system, which is far more expensive than systems of comparable quality in other countries. The Affordable Care Act made incremental progress in this direction, but something like a national single-payer system is necessary to relieve cost pressures on both states and the federal government. A first step along that road would be to make Medicaid a fully federally run program, analogous to Medicare, as has been proposed by Greg Anrig of the New America Foundation.

• Education: Because education is the most localized category of social spending, it will be the most difficult to address—but because it makes up the largest component of non-federal spending, it is also the most important. In the near term, demanding infusions of federal support for local education could go a long way toward equalizing access to education. In the long run, we should not lose sight of the inequality that inevitably results from allowing schools to be funded and administrated locally, nor should we take that localism as a necessity. In the past, the Supreme Court has held that education is not a fundamental right, and that a system of unequal K-12 school systems funded by local property taxes is constitutional. But our fragmented and unequal educational system is a strange and inferior institution compared to what exists in other rich countries.

Who will do it?

Much has changed since the 1960s. The Cloward-Piven strategy was articulated in the context of the civil rights movement and the militant welfare rights campaign that arose in its wake. The strategy was formulated in a time of affluence, when the Democratic Party was still deeply committed to social spending.

And yet, though the Left has been in retreat for decades, there are signs of life from which new coalitions can be cobbled together: the emergence last fall of the Occupy movement, and more recent labor insurgencies. We propose that protest-oriented movements such as Occupy, organized labor and progressive elected officials at the state and local level form a motley, but powerful, anti-austerity coalition.

• Occupy Wall Street: Occupy began as a largely youth-based movement, reflecting the frustration of young people facing rising inequality and diminishing economic prospects. The recession hit this demographic especially hard, and its effects will continue to follow them throughout their lives. Those who have entered the job market in recent years face lower employment rates, worse wages and higher debts than those who preceded them. Occupy was a reaction to this, and it reflects a broader shift to the left among Americans under 30.

The actual Occupy movement has left the streets. It did, however, unleash a wave of politicization that remains with us. The labor and community struggles of the last year bear its mark. Thousands of people are still active in groups that found their genesis in Occupy. The idea that elites use their wealth and power to the detriment of the vast majority of people has introduced a level of class analysis into the national public debate that hasn’t been seen in 80 years.

The early success of Occupy owed much to a creative wellspring from the anarchist movement. The novel idea of occupying space and creating camps is testimony to that. But too many within the movement saw those encampments as models of a future post-capitalist utopia, rather than merely tactical deployments. Not surprisingly, they failed to connect these tactics to a wider political strategy.

Occupy’s failure in this respect and its inability to translate last fall’s energy into more sustained organizing around a broad anti-austerity message reflects both historical—and innate—weaknesses within the anarchist movement and activists’ fears of being co-opted into a neoliberal electoral framework.

By linking younger activists on the extra-parliamentary Left with labor unions and policymakers under an umbrella program that’s both radical and achievable, Occupy activists could contribute to tangible progressive change without sacrificing their uncompromising zeal. And the adventurous (and at times extra-legal) spirit of Occupy can foster a radical rank-and-file-led workers’ movement.

• Organized Labor: Today, only 12 percent of the workforce belongs to labor unions. However, 37 percent of public employees are unionized, compared to just 7 percent in the private sector. This is both a striking sign of the American Left’s decline and a reason why resistance to the current economic crisis has been hard to muster.

That the public sector houses what remains of the labor movement is taken by many to be an indication of the movement’s terminal decline. Fittingly, even this last union bastion is eroding.

Cash-strapped states and cities have launched an effective bipartisan attack on the salaries, benefits and collective bargaining rights of public workers. Scott Walker’s victory in Wisconsin was just the most flamboyant example of a generalized phenomenon. In the context of local competition over resources and general economic downturn, public employees are easy targets.

The strength of a middle-class politics built around resentment should not be underestimated: Walker had a real social base, and thousands were energized around anti-union sentiment. His supporters saw union pensions, health benefits and worker protections as special privileges stolen from more productive sectors in the private economy, rather than as the just rewards for hard labor that everyone deserves. Even some liberals, sympathetic to unions in the private sector, view the interests of unionized public employees and the interests of the public they serve as being irresolvably conflicted.

Instead of asking, “Why not me?” this anti-working class alliance demands, “Why them?” For this precise reason, shifting fiscal burdens from underwater state and local budgets onto firmer, federal terrain is vital. But in the mean- time, we should accept that the labor movement is now concentrated in the public sector. While this poses difficult challenges, it can also be turned into a source of strength.

Some see public-sector unions as little more than cartels that protect the privileges and pay of their members. But these unions can be a progressive voice demanding a government that works not just for its employees, but for society as a whole. And if the public sector was more stable, with its jobs linked to politically untouchable and universal federal programs, public-sector unions could have clout similar to that of their powerful European counterparts, visible and reliable protectors of the welfare state.

Historically, public-sector unions are more oriented than their private-sector counterparts toward a social-movement unionism—connecting organically with their communities rather than limiting their struggles to shop-floor level disputes. This broader orientation was critical to the mass local support the Chicago Teachers Union garnered in its recent struggle. By devoting significant resources toward community outreach and tying its demands to a vision of egalitarian public education, the union made the strike about more than just wages and benefits.

The other component of a potential labor contingent can be found in groups like Working America, an allied organization of the AFL-CIO that boasts 3 million members. Though the group’s potential is largely untapped, by using Working America as its proxy, the AFL-CIO is able to circumvent restrictive labor laws and build alliances with both non-union workers and the unemployed. Actions pitched at this community level can show the public that unions are more than self-interested actors and make labor a cornerstone of a broader progressive movement.

The labor movement also has the ability to connect the outsider power of protest with the insider business of writing and lobbying for legislation. Unions have both the resources and the experience to help create policies and move lawmakers. This will be a necessity for any movement that seeks to reshape the structure of the American welfare state, an important complement to the visibility and disruptive potential of street protest.

• Local and State Officials: Our strategy would generate political pressure first and most intensely at the state and local levels. The recent neoliberal and technocratic drift of local governments has much to do with their intense budget constraints.

Our era lacks the robust urban political coalitions that characterized the period when the Cloward-Piven manifesto was written. At that time, the civil rights movement was able to forge alliances between urban people of color and affluent, educated white liberals—often against working-class political machines that excluded non-whites. Today, however, elite liberals are arrayed against what they regard as the modern machine: a “bloated” public sector—a sector that has become one of the only sources of stable, middle-class jobs for people of color. Neoliberal mayors such as New York’s Michael Bloomberg and Chicago’s Rahm Emanuel unapologetically represent the interests of wealthy business owners against the working class, pushing austerity and privatization as the solutions to fiscal crisis. Breaking the power of this political bloc will necessitate offering fiscally stressed governors and mayors an alternative path.

State and local officials are generally happy to have the burden of social spending taken off their hands, whatever their nominal ideological commitments. The Right may have denounced Obama’s stimulus bill, but most Republican governors and mayors didn’t turn down the money.

If progressives can articulate a positive political vision while simultaneously pushing for policies to ease the fiscal burden on states and cities, they will offer voters and officials an alternative that is appealing and practical. While refusing to sacrifice public services or jobs on the altar of balanced budgets, the Left could ally with state and local leaders to lobby for national solutions to fiscal crisis.

The road to social democracy

The Left must not only defeat austerity and preserve the social safety net; it must do so in such a way that assembles the forces necessary for more fundamental transformations in the future.

This vision should be premeditated. We can’t go back to the post-war golden age of the American welfare state, but we can build a system in the 21st century that embodies what people remember most from that era—an overriding sense of freedom. Freedom to give their children an education without rival. Freedom from poverty, hunger and homelessness. Freedom to grow into old age with pensions, Social Security, and affordable and accessible healthcare. Freedom to leave an exploitative work environment and find another job. Freedom to organize with fellow workers for redress.

These memories are somewhat false ones:

The welfare state has never been so universal. But the appeal of such a society, combined with the political strategy needed to make it a reality, will pave the way for the institution of a new set of economic and social rights to complement our bedrock political and civil rights.

Even greater democratic horizons lie beyond that.

No comments:

Post a Comment