Thursday, June 21, 2012

The Once and Future Liberalism

We need to get beyond the dysfunctional and outdated ideas of 20th-century liberalism.

Walter Russell Mead

Writing about the onset of the Great Depression, John Kenneth Galbraith famously said that the end had come but was not yet in sight. The past was crumbling under their feet, but people could not imagine how the future would play out. Their social imagination had hit a wall.

The same thing is happening today: The core institutions, ideas and expectations that shaped American life for the sixty years after the New Deal don’t work anymore. The gaps between the social system we inhabit and the one we now need are becoming so wide that we can no longer paper over them. But even as the failures of the old system become more inescapable and more damaging, our national discourse remains stuck in a bygone age. The end is here, but we can’t quite take it in.

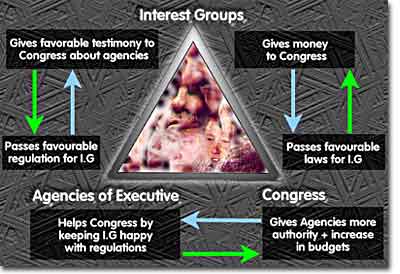

In the old system, most blue-collar and white-collar workers held stable, lifetime jobs with defined benefit pensions, and a career civil service administered a growing state as living standards for all social classes steadily rose. Gaps between the classes remained fairly consistent in an industrial economy characterized by strong unions in stable, government-brokered arrangements with large corporations—what Galbraith and others referred to as the Iron Triangle.

In United States politics, the iron triangle is a term used by political scientists to describe the policy-making relationship among the congressional committees, the bureaucracy (executive) (sometimes called "government agencies"), and interest groups.

For example, within the federal government the three sides often consist of: various congressional committees, which are responsible for funding government programs and operations and then providing oversight of them; the federal agencies (often Independent agencies), which are responsible for the regulation of those affected industries; and last, the industries themselves, as well as their trade associations and lobbying groups, which benefit, or seek benefit, from these operations and programs.

Probably the earliest concept of the "iron triangle" was on January 17, 1919 by Ralph Pulitzer. It was the post World War I era when Pulitzer wrote about the Paris Peace Conference and the new relationships between the allied Governments.[1] He stated,

- “Three forces are laboring for such a sinister peace: (1) the bourbonism of politicians…; (2) the materialism of industrial…; (3) the militarism of professional soldiers…” and “If the Peace Conference is allowed to remain between governments instead of between peoples it is apt to degenerate…”

____________________________________________________________________________________

High school graduates were pretty much guaranteed lifetime employment in a job that provided a comfortable lower middle-class lifestyle; college graduates could expect a better paid and equally secure future. An increasing “social dividend”, meanwhile, accrued in various forms: longer vacations, more and cheaper state-supported education, earlier retirement, shorter work weeks, more social and literal mobility, and more diverse forms of affordable entertainment. Call all this, taken together, the blue model.

In the heyday of the blue model, economists and social scientists assumed that from generation to generation Americans would live a life of incremental improvements. The details of life would keep getting better even as the broad outlines of society stayed the same. The advanced industrial democracies, of which the United States was the largest, wealthiest and strongest, had reached the apex of social achievement. It had, in other words, defined and was in the process of perfecting political and social “best practice.” America was what “developed” human society looked like and no more radical changes were in the offing. Amid the hubris that such conceptions encouraged, Professor (later Ambassador) Galbraith was moved to state, in 1952, that “most of the cheap and simple inventions have been made.”1 If only the United States and its allies could best the Soviet Union and its counter-model, then indeed—as a later writer would put it—History would end in the philosophical sense that only one set of universally acknowledged best practices would be left standing.

Life isn’t this simple anymore. The blue social model is in the process of breaking down, and the chief question in American politics today is what should come next.

One large group, mainly “blue state” self-labeled liberals who think the blue model is the only possible, or at least the best feasible, way to organize a modern society, wants to shore it up and defend it. This group sees the gradual breakup of the blue social model as an avoidable historical tragedy caused by specific and reversible policy errors. Supporters of the model point to the rising inequality and financial instability in contemporary American life as signs that we need to defend the blue system and enlarge it.

Others, generally called conservatives and often hailing from the “red states”, think the model, whatever its past benefits or general desirability, is no longer sustainable and must give way to an earlier, more austere but also more economically efficient pre-“big government” model. Often, backers of this view see the New Deal state as a great wrong turn. Their goal is to repair the errors of the 1930s and return to the more restrictive constitutional limits on Federal power from an earlier time.

But even as the red-blue division grows more entrenched and bitter, it is becoming less relevant. The blue model is breaking down so fast and so far that not even its supporters can ignore the disintegration and disaster it now presages. Liberal Democrats in states like Rhode Island and cities like Chicago are cutting pensions and benefits and laying off workers out of financial necessity rather than ideological zeal. The blue model can no longer pay its bills, and not even its friends can keep it alive.

Our real choice, however, is not between blue or pre-blue. We can’t get back to the 1890s or 1920s any more than we can go back to the 1950s and 1960s. We may not yet be able to imagine what a post-blue future looks like, but that is what we will have to build. Until we remove the scales from our eyes and launch our discourse toward the future, our politics will remain sterile, and our economy will fail to provide the growth and higher living standards Americans continue to seek. That neither we nor the world can afford.

The blue social model rested on a novel post-World War II industrial and economic system. The “commanding heights” of American business were controlled by a small number of sometimes monopolistic, usually oligopolistic firms. AT&T, for example, was the only serious telephone company in the country, and both the services it offered and the prices it charged were tightly regulated by the government. The Big Three automakers had a lock on the car market; in the halcyon days of the blue model there was virtually no foreign competition. A handful of airlines divided up the routes and the market; airlines could not compete by offering lower prices or by opening new routes without government permission. Banks, utilities, insurance companies and trucking companies had their rates and, essentially, their profit levels set by Federal regulators. This stable economic structure allowed a consistent division of the pie. Unionized workers, then a far larger percentage of laborers than is the case today, got steady raises in steady jobs. The government got a steady flow of tax revenues. Shareholders got reasonably steady dividends.

There were problems with the blue model. It abided systematic discrimination against women and minorities, and a case can be made that it depended on that discrimination to some degree. Consumers had little leverage: If you didn’t like the way the phone company treated you, you were free to do without phone service, and if you didn’t like poorly made Detroit gas guzzlers that fell apart in a few years, you could get a horse. The system slowed innovation, too; AT&T discouraged investments in new telecommunications technologies. Rival companies and upstart firms were barred from controlled markets by explicit laws and regulations intended to stabilize the position of leading companies. By some accounts, too, the quarter century after World War II was a period of stultifying cultural conformity. In this prologue to the end of History, some “last men”, from the Beatniks to Lennie Bruce to Andy Warhol to Lou Reed, were already bored, resenting the pressure to conform that the mass consumption, Fordist era entailed.

The blue model began to decay in the 1970s. Foreign manufacturers recovered from the devastation of World War II and in many cases had more efficient and advanced factories than lazy, sclerotic American firms. German and Japanese goods challenged American automobile and electronic companies. The growth of offshore financial markets forced the U.S. financial services industry to become more flexible as both borrowers and lenders were increasingly able to work around the regulations and the oligopolies of the domestic market. Demand for new communications services created an appetite for competition against Ma Bell. The consumer movement attacked regulations designed to protect big companies. As a sign of the times, Ted Kennedy, of all people, cosponsored a bill to deregulate the airlines. Anti-corporate liberals rebelled at the way government power and regulation allowed corporations to give consumers the shaft. The new environmental movement pointed to the problem of privately caused but publicly paid-for externalities like air and water pollution.

As the old system dissolved, companies had to become more flexible. As industry became more competitive, private-sector managers had to shed bureaucratic habits of thought. Lifetime employment had to go. Especially productive workers had to be lured with high pay. The costs of unionization grew; in the old days, government regulators simply allowed unionized firms to charge higher prices to compensate for their higher wage costs, but that no longer worked in the face of greater competition. High wages in the United States drove manufacturers toward greater automation even as low wage labor in Asia and elsewhere began to make inroads in manufacturing. And with the advent of the pro-deregulation Reagan Administration, government enthusiasm for maintaining the Iron Triangle waned dramatically, coincidentally dividing the Republican Party into pro- and anti-big business wings as never before since the first Gilded Age.

Some companies (like the automakers) were large and rich enough to cling to the blue model long after its sell-by date. The result was a long, slow and grueling decline whose late stages are still unfolding today. The Big Three lost (and are still losing) market share to more nimble rivals. Their unionized workforce became old, inflexible and expensive, and they were supporting ever larger numbers of retirees on the basis of smaller market shares and shrinking profitability. These days, most private-sector blue companies can only survive with government support. Government protection from foreign competition (economically wasteful and illegal under our international trade agreements) is one option; direct subsidies and cash transfers (bailouts and tax breaks) is another. Neither works very well or for very long. Both are unsustainably expensive given current levels of national debt.

Demographic change is accelerating the crisis of the blue social model, as retirement and other social benefits come under increasing pressure. Social Security and Medicare are covering a steadily growing percentage of the population. Younger workers no longer believe these systems will be in place for their old age. They are at least partly right. Without major change, the current Medicare system cannot last. Beyond that, a general crisis of the pension system threatens to reduce the income of older people even as government is less able to take up the slack. Defined benefit retirement programs have largely disappeared in the private sector; state and municipal pensions threaten to bankrupt some cities and states, and they are forcing officials in others to choose between drastic service cuts and breaking pension commitments to retirees.

With some significant variation, the welfare-state economies of Western Europe have also been true blue, and they have consequently encountered the same limits and entered the same systemic crisis as the U.S. system. In a sense, the European situation is worse. It is structurally bluer than America, as measured by public share of GDP and the extent of “cradle-to-grave” services proffered. Demography is a graver problem in the European welfare states than in the United States, and the poor design of the European monetary union has further exacerbated the crisis in many countries.

There are a lot of reasons to be nostalgic for the old days (especially for the white males who were, far and away, the biggest beneficiaries of the old system), but there are also good reasons to bid the blue model good riddance. It wasn’t a particularly inspiring system. There was actually a lot that was unjust and cramped about the blue social model, and the friends of progress and the average person should be chomping at the bit to put something better in its place. Even in the early days of the blue social model, after all, social critics pointed to mass assembly line production as a dehumanizing innovation that condemned millions to a wage slavery of repetitive, meaningless, soul-killing work to produce endless streams of mediocre consumer products.

Fordism was once a term of abuse hurled at the factory system by Marxist critics who, rightly, deplored the alienation and anomie that mass production for mass consumption entailed. Has the Fordist factory system and the big box consumerism that goes with it now become our ideal, the highest form of social life our minds can conceive? Social critics also denounced our school system, justifiably, as a mediocre, conformity inducing, alienating, time wasting system that trained kids to sit still, follow directions and move with the herd. The blue model built big-box schools where the children of factory workers could get the standardized social and intellectual training necessary to enable most of them to graduate into the big-box Ford plant and shop in the big-box store. Maybe that was a huge social advance at one time, but is that something to aspire to or be proud of today? Don’t we want to teach our children to do something smarter than move in large groups by the clock and the bell, follow directions and always color between the lines?

Finally, in this regard, the blue model has impoverished our lives and blighted our society in more subtle ways. Many Americans became (and remain) stuff-rich and meaning-poor. Many people classified as “poor” in American society have an historically unprecedented abundance of consumer goods—anything, essentially, that a Fordist factory here or abroad can turn out. But far too many Americans still have lives that are poor in meaning, in part because the blue social model separates production and consumption in ways that are ultimately dehumanizing and demeaning. A rich and rewarding human life neither comes from nor depends on consumption, even lots of consumption; it comes from producing goods and services of value through the integration of technique with a vision of social and personal meaning. Being fully human is about doing good work that means something. Is a blue society with our level of drug and alcohol abuse, and in which the average American watches 151 hours of television a month, really the happiest conceivable human living arrangement?

In any event, there is no going back to blue, and using public resources to try to prop up the old system is a waste of those resources and a hurtful diversion from the need to figure out what we need to do next. Europe’s challenges are complicated mightily by an unfinished and perhaps impossible federal project (too large a subject to analyze here in depth). American society, for its part, must move beyond the increasingly dysfunctional and outdated ideas of 20th-century liberalism. If we don’t, economic decline and social stagnation will undercut our prosperity, endanger our liberty and undermine our international power and domestic security. That is a future no true liberal could love.

The real crisis today in the United States is the accelerating collapse of blue government, not blue private industry, which is a phenomenon largely behind us. We are witnessing a multi-dimensional meltdown that affects our lives and politics in many ways. Three elements of the blue government meltdown in particular are worth mentioning.

The first is the government’s role in providing the benefits associated with the blue system. When we talk about “runaway entitlement programs”, we are talking about commitments by the government to provide retirement and other social benefits that originated as part of the blue system social contract. Workers could retire as early as 62 with a combination of Social Security and private pensions. These costs are now exploding according to the immutable logic of demographic and actuarial facts, and it is clear that the government can’t pay them into the future.

The second crisis is that the government is now the last “true blue” employer in the country. Federal, state and local governments are often staffed by lifetime civil servants whose jobs are protected by law and by some of the last truly powerful unions in the country. All the Reagan Administration and like-minded state governments ever managed to do was to slow the growth of government, not reduce it; government at all levels today accounts for a larger share of U.S. gross national product than it did in 1981 (and that was when government did a lot more in regulating the economy). It has become incredibly expensive for governments to do anything at all, and they are poorly equipped to respond nimbly to the fast-changing conditions of America today.

Quasi-governmental sectors of the economy (like the health and university industries) are also mainly blue: characterized by high wages, stable employment, cumbersome procedures, and powerful non-industrial (or “trade”) unions that “produce” only paper and process, imposing high transactional costs to the economy. The result is a governmental sector too unproductive, too unresponsive and too expensive to do what needs to be done at a reasonable cost. Government also retains the anti-consumer mentality of the old blue monopolies: If you don’t like the lousy services government provides, you can...move. This is why public schools are increasingly expensive and yet do not provide improved services. Education, health care, the legal system and government are four crucial economic sectors in which costs have been rising faster than inflation for much of the last generation.

Finally, culturally and intellectually, bureaucrats and politicians often remain blue. Despite the ebbing of the blue private sector, they think instinctively in the old ways, come up with blue solutions to non-blue problems (think the Obama Administration’s approach to health care costs), and often fail to grasp either the constraints or the opportunities of the new era.

As long as the Federal government can print money and find lenders to buy its bonds, it can bleed slowly. It can watch its fiscal position erode gradually, and only gradually become less effective and popular. But state and local governments increasingly need vast transfers of cash from the Federal government to keep their blue noses above the rising tide. The stock market declines after September 2008 wiped out huge chunks of the wealth that state pension systems needed to have even a hope of paying the pensions promised to government retirees under terms more generous than virtually any private employers now provide. California and New York are headed over the cliff without Federal bailouts, and others are following close behind. That is why a substantial share of the Obama Administration “stimulus” spending was targeted less at New Deal-era infrastructure projects than at simply keeping unsustainable state bureaucracies and systems afloat for a few months or years longer.

There are several ugly truths that the country (and especially those states whose governments are bigger and bluer than the rest) must soon face. One concerns taxes. The debate today at the elite level is about whether the rich should pay more. Given the historic lows of marginal and capital gains tax rates, this is a debate of consequence for reasons having to do with fairness. But it distracts attention from a more fundamental political reality: Voters simply will not be taxed to cover the costs of blue government, and in most cases they will vote out of office anyone who suggests otherwise.2 That, at base, is what the Tea Party movement is all about. Voters with insecure job tenure and, at best, defined-contribution rather than defined-benefit pensions simply refuse to pay higher taxes so that bureaucrats can enjoy lifetime tenure and secure pensions.

Second, voters will not accept the shoddy services that blue government provides. Government must respond to growing consumer demand for more user-friendly, customer-oriented approaches. The arrogant lifetime bureaucrat at the Department of Motor Vehicles is going to have to turn into the Starbucks barista offering service, and options, with a smile.

Third, government must reconcile itself to its declining ability to manage a post-blue economy with regulatory models and instincts rooted in the past. We need to be thinking about structural changes based on properly aligned incentive architecture, not regulatory systems based on command protocols.

The collapse of a social model is a complicated, drawn out and often painful affair. The blue model has been declining for thirty years, and the final bell has not yet tolled. But toll it will, and as the remaining supports of the system erode, slow decline and decay is increasingly likely to give way to headlong crash. That may be happening now; the financial mess that came upon us in the fall of 2008 may be both symptom and accelerant (not cause) of the basic problem.

One of the main reasons Americans have been so slow to recognize the collapse of the blue model is that the language we use to discuss and think about politics tends to disorganize our stock of understanding about our own society. Millions of Americans are conservatives and even reactionaries but think of themselves as “liberals”; at the same time, millions of genuine liberals and even radicals call themselves conservative. It’s an unholy mess that calls desperately for a language intervention. Let us begin with an historic meditation on the “L” word.

“Liberal” and “progressive” are two of the noblest and most important words in the English dictionary. They describe essential qualities of the American mind and essential values in American politics in a country born in reaction against oligarchy and concentrated autocracy. They sum up in a nutshell what this country is all about. A liberal is someone who seeks ordered liberty through politics—namely, the reconciliation of humanity’s need for governance with its drive for freedom in such a way as to give us all the order we need (but no more) with as much liberty as possible. In this sense, liberty isn’t divided or divisible into freedoms of speech, religion, economic activity or personal conduct: Genuine liberals care about all of the above and seek a society in which individuals enjoy increasing liberty in each of these dimensions while continuing to cultivate the virtues and the institutions that give us the order without which there can be no freedom.

But today the words liberal and progressive have been hijacked and turned into their opposites: A “liberal” today is somebody who defends the 20th-century blue social model; a “progressive” is now somebody who thinks history has gone wrong and that we must restore the Iron Triangle of yesteryear to make things better. Most of what passes for liberal and progressive politics these days is a conservative reaction against economic and social changes the Left doesn’t like. The people who call themselves liberal in the United States today are fighting rearguard actions to save old policies and established institutions that once served noble purposes but that now need fundamental reform (and in some cases abolition), lest they thwart the very purposes for which they were created.

This is not the first time such a reversal around the word liberal has taken place. To the contrary, there is a long history of specific political agendas that incorporate a forward-looking program and bear the name liberal precisely because they look ahead in the name of the nation as a whole. As time goes by they make their contributions and society goes on to face new issues. The old “liberal” becomes the new “conservative” and fresher, more useful ideas emerge to capture the label. Old liberalisms are born to perish as new, more vital liberalisms take up the struggle; in the process the liberal spirit itself lives on.

We can see this process at work in modern Anglo-American history, during which liberalism has gone through at least four distinct incarnations. Liberalism 1.0 was the political expression of the original Enlightenment philosophy that developed in Britain and shaped the Glorious Revolution of 1688. That Revolution remains the seminal political event in the history of the English-speaking world. The American Founding Fathers set out consciously to imitate the spirit of 1688. Both the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights flow from the ideas of a revolution that once and for all made Parliament supreme over the Crown in British history.

But the Revolution of 1688 had its limits, and by 1776 liberalism 1.0 was no longer enough. In Britain, the corruption of the House of Commons allowed George III to reassert royal control; Americans realized that the constitutional monarchy of liberalism 1.0 was no longer ideal. The 2.0 liberalism of our Founding Fathers replaced constitutional monarchy with a republic expressly founded on natural rights and the sovereignty of the people. The 1.0 Revolution of 1688 had replaced an intolerant established Church with one constitutionally more tolerant; the 2.0 American Revolution of 1776 separated the church from the state to the benefit of both.

Liberalism 2.0, as developed in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, was rooted in the thought of 1.0 liberals like John Locke. But Adam Smith, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and George Washington developed and put into practice a set of ideas about how individual liberty could be reconciled with economic development and good governance. Note how the names changed. In 1688, if you supported the Glorious Revolution you were a Whig and a liberal. In 1776, if you supported those same principles against the Declaration of Independence you were a Tory conservative.

Yet while liberalism 2.0 was more advanced and more fully and consistently liberal than the 1.0 model, 2.0 liberals remained tied to many ideas later liberals considered anathema. The American Founders, for example, thought that limiting the vote to rich white men was just fine; women and the “lower orders” had no legitimate place in public life. While 2.0 liberals understood that slavery was an evil (much more so than the 1.0 liberals), they believed that it could be tolerated until it died a natural death.

The 19th century saw the development of liberalism 3.0. Sometimes called Manchester liberalism, this was, compared to the earlier systems, a philosophy of radical individualism and equality. The 3.0 liberals had much more confidence in the common-sense reasoning power of ordinary people than earlier generations. Their programs included once unthinkable ideas like universal suffrage, the abolition of slavery, an end to state-enforced monopoly corporations, limited government, free markets at home and free trade abroad. 3.0 liberals tended to support strong, personal and emotional religious belief; they were much more likely to be evangelical than either 1.0 or 2.0 liberals. Like earlier liberals, 3.0 liberals believed that capitalism, individual rights and a culture of virtue supported by a tolerant, non-fanatical Protestant Christianity could provide ordered liberty. (They also, by and large, believed in the superiority of the white race, thought that “too much” Jewish influence was bad and believed that Catholic countries could never become effective modern democracies.)

In the 20th century, liberals continued to seek new ways of advancing the core liberal synthesis of individual freedom with social order. Before the Depression and World War II, liberalism 4.0 reflected the progressive ideas of men like Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. As a result of the New Deal and World War II, turn-of-the-century progressivism was revamped and retweaked into liberalism 4.1, the big government, Iron Triangle system that most Americans think of when they hear the word “liberal” today. Today liberalism 4.1, blue liberalism, is increasingly outdated and backward-looking, but in its time it was a genuinely positive attempt to realize old values in new circumstances, and many of its achievements still demand our respect. The driving force shaping the agenda of 4.0 and 4.1 liberals before and after the New Deal were a series of powerful and profound historical developments that changed the world under their feet. The earlier versions of liberal politics had been built in societies that, while beginning to urbanize and industrialize, were still predominantly agricultural. Both Jeffersonian and Jacksonian liberals saw independent small farmers as the basis of American freedom and democracy.

All that began to change after the Civil War. The Industrial Revolution and associated phenomena (urbanization, mass immigration from non-English speaking, non-Protestant societies and the economic decline of small farmers and rural communities) presented liberals with new problems: urbanization, class conflict (and the competition with socialism for the support of urban industrial workers), assimilation and the regulation of a modern industrial economy. These extremely complex problems posed challenging questions about the basic premises of liberal thought. Classically, liberals considered an unholy alliance of church and state as the prime enemy of freedom. In the late 19th century, however, the rise of huge industrial corporations seized pride of place as a threat to individual liberty; 20th-century, 4.0 liberals began to think about the state as a possible ally to defend individuals from unaccountable private power. The liberalism of Theodore Roosevelt and men like William Allen White was defined by their response to these challenges. Democratic government needed to ensure a level playing field, to fight for basic equality of opportunity.

There were other problems, too, and they grew after World War I. Agrarian America had been a relatively egalitarian society when it came to incomes; the Industrial Revolution and mass immigration threatened to divide society into paupers and millionaires. Agrarian America had also been relatively homogeneous in culture: Protestant and British, or from relatively similar cultures in northern Europe, like those of Germany and the Netherlands. A society including millions of impoverished urban workers from radically different cultural backgrounds could not be run as in the past; the situation grew even more complex as millions of African Americans left Dixie for big Northern and Midwestern cities.

The progressives and liberals who created 20th-century liberalism did their best to address these and similar problems in ways that would preserve as much as possible of the old liberal heritage in a new world. The development of a professional, bureaucratic civil service and the regulatory state were intended to preserve individual autonomy and dignity in a world dominated by large and predatory corporate interests. At the same time the challenges of modernization and urbanization (public health, food safety, and provision of newly necessary services like electricity and gas) could best be met through public services and, in some cases, regulated private monopolies. The emerging professional and managerial classes were not just middle classes in the sense of standing between the rich and the poor in income and status; they were mediating classes who sought through the state, the universities and the learned professions to erect a balance between the interests of the wealthy and those of the workers.

On religion, 4.1 or blue liberals were better than their predecessors at understanding the ways in which growing numbers of American Catholics and Jews could support rather than undermine the culture of faith and virtue on which American civil liberty ultimately depends. Partly to create a neutral public space in which Catholics and Jews could join Protestants on equal terms in debate, blue liberals tended to favor the secularization of public life. Despite some missteps and excesses along the way, when it came to both gender and (perhaps their greatest accomplishment) race, blue liberals did yeoman service to the cause of human freedom by opening the doors of full participation more widely than ever before. Their great effort to open the gates of American opportunity to non-whites, with special attention to African Americans, was one of the greatest triumphs ever of the American liberal spirit.

Although socialists and social democrats sometimes made common cause with 4.1 liberals, at bottom, blue liberalism was built as an alternative to socialism rather than an on-ramp for it. With the onset of the Great Depression in particular, most American liberals came to believe that providing benefits like Social Security and unemployment insurance would inoculate American workers against more virulent forms of socialist ideology and attract new immigrants and their children toward the American liberal tradition. It worked. The strong socialist movements, mostly based among recent immigrants from countries with strong socialist and social-democratic traditions, gradually faded away. The descendants of the European immigrant waves between 1880 and 1920 turned their backs on socialism, and the overwhelming bulk of the American labor movement was strongly anti-communist throughout the Cold War.

The second phase in the construction of what became the blue liberalism of the past two generations owed much to the emergency mentality of both the Great Depression and World War II. Programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps and later the GI Bill, along with the experience of mobilization and rationing during the war, convinced many liberals that government could and should do more than ensure a level playing field, that it could plan, regulate and control well enough to at least bracket a rough equality of economic and social outcomes, not just opportunities. The historically high rates of taxation during World War II were largely maintained during both the Truman and Eisenhower Administrations in order to finance what became the regulatory state of the Iron Triangle. In time, with the advent of the Great Society programs of “the best and the brightest”, liberalism 4.1 became more explicitly redistributionist, and more deeply convinced of the superiority of the technocratic ethos. Thus President John F. Kennedy at Yale University in June 1962:

The central domestic issues of our time . . . relate not to basic clashes of philosophy or ideology but to ways and means of reaching common goals—to research for sophisticated solutions to complex and obstinate issues. . . . What is at stake in our economic decisions today is not some grand warfare of rival ideologies which will sweep the country with passion, but the practical management of a modern economy.

What we need is not labels and cliches but more basic discussion of the sophisticated and technical questions involved in keeping a great economic machinery moving ahead.

Uniting all the versions of liberalism since 1688 has been a drive to find a creative compromise between the individual’s drive for self-expression and freedom and the need for a stable society. Liberalism insists that an open, dynamic society will lead to a better life for all, and that promoting ordered liberty is the morally obligatory as well as the pragmatically desirable thing to do.

All four versions have something else in common: None can serve as the political program for the heirs of the two great revolutions today. We don’t want the constitutional monarchy and Anglican establishment of William III; we don’t want the aristocratic, limited-franchise republic of George Washington; we don’t want the Manchester liberalism of the 1860s; and we don’t want the managerial state that liberals and progressives built in the first two-thirds of the 20th century. That doesn’t mean we should not admire, learn from and build on each of these liberal traditions, but our job today is to synthesize enduring liberal values in a 21st-century liberalism 5.0.

As with earlier versions, liberalism 5.0 must build on the best of what has gone before while making adjustments—radical when necessary, though never gratuitously so—to existing beliefs and institutions. 5.0 liberals must challenge the right of blue liberals to own the L-word, seeking both to convince 4.1 liberals to come back to the future and denouncing those who won’t as the blinkered reactionaries and speed bumps they are.

These conversions are not as rare as one might think. Benjamin Franklin was one of the most prominent American 1.0 liberals during much of his life. During his long residence in London he hoped that a Transatlantic British Empire under the royal House of Hanover would be a beacon of enlightenment to all the world. But as times changed, so did Franklin; he became a 2.0 liberal and one of the most courageous and effective leaders of the American Revolution. Some of the most important and creative people who will lead the movement toward a 5.0 America will have grown up steeped in the values of 4.1 thought.

Developing a politically successful liberalism 5.0 must start with an understanding of what the people want. Americans may be conflicted, but we are not particularly complicated. In a big-picture sort of way, the American people have a Maslovian hierarchy of needs, and we want our political leaders to meet them all. By and large, American voters want five things. First, above and before all else, they want physical safety for themselves, their loved ones and their property. Americans generally expect American politicians to pass a credibility test on this issue before hearing them out on other issues. That is unlikely to change.

Second, Americans want and expect rising standards of living. Times when the economy fails to deliver the growth Americans expect tend to be politically tough: like the depressed years of the 1880s and early 1890s and, of course, the Great Depression. And now.

Third, Americans want honor. We don’t want to be dissed by foreigners and we want to be free, equal and in charge of our own lives at home. We don’t like plutocrats, snooty social hierarchies, privileged hereditary ruling elites, or intellectual and moral poobahs telling us how to live. We despise being at the mercy of large, unfeeling corporations. We don’t like having our privacy violated by public or private snoops. We hate standing at the DMV line like humble peasants as officious bureaucrats abuse their authority. We also believe, deeply and viscerally, that the commonsense reasoning of the average person is enough to resolve political and moral questions, and we don’t like experts who try to impose counterintuitive policy ideas (that deficits are good for you, for example).

Fourth, Americans want to feel that the United States of America is on track to fulfill its global mission, whatever that is (and our thinking here lately tends toward the fuzzy). But Americans generally feel that this exceptional country has some kind of unique world role, and they want their political leaders to keep the country on the right course.

Finally, Americans want to believe that all four goals work together: that defending their security, promoting their prosperity, preserving their freedom and equality and fulfilling their global mission are all part of an integrated package and worldview—and that the commonsense reasoning of the average American can understand the way the pieces fit together. They are, in other words, looking for more than a set of unrelated policies that accomplish certain discrete goals: They want those policies to proceed from an integrated and accessible vision that meshes with their understanding of traditional American values and concerns.

A generation ago, blue liberalism was pretty good at giving most of the people what they wanted, and between 1932 and 1968 blue liberals dominated American politics. From FDR to JFK (and LBJ until the Vietnam War went wrong and inflation got out of hand), liberal Democrats impressed most Americans with their ability to manage national security, build prosperity, honor the dignity of the common man and lead the world on the basis of a reasonably consistent and coherent worldview. The one Republican who managed to get elected President during the only period of stable Democratic power since the Civil War was Dwight Eisenhower, a man who could have won the Democratic nomination in 1952 if he had wanted it, and who accepted the basic New Deal policies of the Roosevelt years and the national security policy of the Truman era.

Since that time, the American political terrain has shifted several times, but it never came to as firm an equipoise as during the quarter century following World War II. From 1968 through 2010 we seem to have been in another era, one in which blue liberal candidates lost more elections than they won. During these years, however, Republican gains have not been consolidated like Democratic gains were during and after the Depression. And the basic reason is that the blue social model of rising living standards based on stable manufacturing jobs for blue collar workers doesn’t work anymore. Automation and outsourcing mean that manufacturing sheds jobs in good times and bad. Rapid technological change and tough international competition force companies to innovate aggressively, and to stay lean. In such circumstances, no party can keep the American people happy for long.

At the same time, the appearance of intellectual elitism widely attributed to blue liberalism has also offended Americans’ sense of dignity and honor. Many people seem to feel that there are too many well-credentialed blue liberals telling Americans things they don’t want to hear and don’t believe—and offering solutions (like much higher energy taxes to solve global warming) that appear to take the interests and concerns of average people lightly. Many blue liberals often argue that the real enemies of average Americans aren’t bureaucrats and Harvard-trained technocrats; they are the financial wizards, evil corporations and plutocratic tycoons. Maybe so, but at this point the argument doesn’t convince many people. Besides, why can’t both be enemies? After all, many elite liberal Democrats, in office and out, have been exceedingly Wall Street-friendly.

What does this argument look like when translated into historical terms? Many believe that the real ideological contest in America today is between “red” liberalism 3.0 (the more individualistic, laissez-faire, often evangelical kind of liberalism of the 19th century) and the more state-oriented, collectively minded post-World War II 4.1 blue liberalism. Red liberals denounce blue liberals as betrayers of the liberal legacy, as ideology thieves who have taken a philosophy grounded in individual freedom and limited government and turned it into a charter for “big” government. Blue liberals respond that red liberals don’t understand how the complexities of modern life make the outmoded pieties of liberalism 3.0 inadequate to today’s problems. But common to both these positions is the belief that the American debate today is between two versions of the past: the (presumed) free market utopia of the 19th century versus the (presumed) social utopia of the New Deal/Great Society of more recent times. If that were true, this would be a nation of conservatives fighting reactionaries—the status quo of 1970 fighting the status quo of 1880.

But it’s not true. Neither aged version of liberalism can adequately address what Americans most want. In particular, neither can provide a new era of rising mass prosperity for the overwhelming majority of the American people. Nobody has a real answer for the restructuring of manufacturing and the loss of jobs to automation and outsourcing. As long as we are stuck with the current structures, nobody can provide the growing levels of medical and educational services we want without bankrupting the country. Neither “liberals” nor “conservatives” can end the generation-long stagnation in the wage level of ordinary American families. Neither can stop the accelerating erosion of the fiscal strength of our governments at all levels without disastrous reductions in the benefits and services on which many Americans depend.

We cannot realistically solve our problems by trying to return to the 3.0 liberalism of the 19th century because the American economy of that era depended on conditions we cannot reproduce today. Though some may think it desirable, we cannot return to a largely agrarian economy. Nor can we replicate the industrial system of the 19th century, with its extremely high tariffs against foreign goods and a completely laissez-faire national attitude toward immigration. Trying to recreate the American economy of a century ago would lead to massive dislocations, depressions and quite likely wars around the world, not to mention thoroughly wrecking the American economy and bankrupting many of our banks and biggest corporations.

But if red liberal fundamentalism can’t work, blue fundamentalism can’t help us either. There’s no going back even half a century ago, because the great achievements of blue liberalism were also rooted in conditions we cannot replicate today. Between 1914 and the 1970s, when the blue social model took shape and rose to power and success, the world economy was in an unusual state. International financial and trade flows were much lower than before 1914 and after 1970, due to the disruptions of two world wars and the Great Depression. And the United States was so far ahead of the rest of the world in manufacturing that few American companies (or workers) had anything to fear from foreign competition. Capital was dramatically less mobile; it was much easier to tax high earners without driving savings and investment out of the country.

At the same time, Americans in the first two thirds of the last century were more willing to engage in group politics than is the case today. Industrial workers fought to build unions and generally voted the way their leaders advised them. Ethnic groups stuck together and voted as blocs. Twentieth-century liberal politics generally involved negotiated agreements among party bosses and other leaders who commanded loyal followings. Few politicians today can count on this kind of unquestioning support in an era when party structures and patronage networks are both weaker and less reliable than they used to be. Now, instead of party structures funding candidates, candidates are expected to fund party structures.

We must come to terms with the fact that the debate we have been having over these issues for past several decades has been unproductive. We’re not in a “tastes great” versus “less filling” situation; we need an entirely new brew. But this is nothing to mourn, because both liberalism 3.0 and 4.0 died of success, just as versions 1.0 and 2.0 did before them.

As for 3.0, rising agricultural productivity ultimately drove millions of farmers off the land; high tariffs helped attract tens of millions of immigrants; ideas and institutions developed in a homogeneous, egalitarian and predominantly agricultural country no longer worked very well in an industrial, urban country threatened by class conflict.

The same with 4.0. Our successful manufacturing economy led us to push for free trade; that stimulated other countries to export to U.S. markets and generated the kind of financial flows that undermined the nation-based Keynesian economic models of the 4.0 econ wizards. The rising affluence of Americans facilitated their mass migration into the suburbs where the old party organizations and ethnic loyalties broke down. More affluent and better educated voters became more individualistic and saw the system of party bosses as an obstacle to democracy rather than a way of making it work. Each version of liberalism in turn created a social system and an economy so dynamic and so inventive that it ultimately outgrew the institutions and ideas that had given it birth. Textbook cases of the cultural contradictions of capitalism at work they were.

Now it has happened again. The success of our institutions and ideas has so changed the world that they don’t work any more. We cannot turn back the clock, nor should we try. America’s job is to boldly go where none have gone before, not to consume our energies in vain attempts to recreate the glories of an unattainable past. We need to do for our times and circumstances what other Americans have done before us: Recast classic Anglo-American liberal thought, still the cultural and moral foundation of American life and the source of the commonsense reasoning that guides most Americans as they evaluate policy ideas and party programs, in ways that address the challenges before us.

For those blue Democrats clinging to liberalism 4.1, this is a time of doom and gloom. For those red Republicans longing for a return to liberalism 3.0, it is a time of angry nostalgia: Ron Paul making a stump speech. This should be a time of adventure, innovation and creativity in the building of liberalism 5.0. America is ready for an upgrade to a new and higher level; indeed, we are overdue for a project that can capture the best energies of our rising generations, those who will lead the United States and the world to new and richer ways of living that will make the “advanced” societies of the 20th century look primitive, backward and unfulfilled.

We’ve wasted too many years arguing over how to retrieve the irretrievable; can we please now get on with the actual business of this great, liberal, unapologetically forward-looking nation?

1According to Candace A. Allen, “The Entrepreneur As Hero”, Economic Insights, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2:1, p. 3, n.d.

2Evidence for this resides in recent Gallup polls, which show that only 21 percent of Americans consider themselves liberals; 40 percent consider themselves “conservative”, and 35 percent call themselves “moderate.’’ Another Gallup poll reports that 49 percent say that the Democrats are “too liberal” while only 38 percent think they are just right; 10 percent think Democrats aren’t liberal enough. After two years in which Democrats controlled the White House and both houses of Congress, using their majorities to pass the most sweeping health and financial legislation in seventy years, only 17 percent said they are happy with the way the country is going.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

WRM, one word: “Recast” (to go boldly…).

Please square this with the history (the existence, even) of Bell Labs.

“Don’t we want to teach our children to do something smarter than move in large groups by the clock and the bell, follow directions and always color between the lines?”

Well, what sort of workers does it take to implement the ISO 900x model that companies aspire to run on these days?

Big Business will not necessarily *lead* to replace the Blue Model. The “Develop and disseminate Best Practices” model needs followers as much or more than leaders.

Schools can concentrate on producing ivory-tower Process Managers divorced from day-to-day production lines, but I’m not sure what good that does. Their endless (and stupefyingly dull) documents are largely ignored by the people who do the actual work, who still depend on tribal knowledge and teaching to master their trade.

Of course, in companies where workers become dependent on their ISO docs like good little followers should, few develop any kind of deep understanding of what they’re actually doing. This soul-destroying situation leads to disaster, as actual competence and understanding becomes less and less common on the floor, as company training moves from a competence-building to a lawsuit-avoiding and ISO-box-checking activity.

“A rich and rewarding human life neither comes from nor depends on consumption, even lots of consumption; it comes from producing goods and services of value through the integration of technique with a vision of social and personal meaning.”

Building cathedrals, being part of the horde of servants that maintained a Great House and its grounds, being part of a conquering army, joining the clergy…

Interesting, how many avenues of personal and corporate meaning are actively discouraged these days by the “culture” that comes out of Hollywood these days. You know, the one that demands conformance to non-conformity, and thus only ends up zooming straight for the lowest common denominator…

Great stuff here, no time to go through it all now.

I must take issue, however, with the contention that conservatives want to restore the economy and society of the 1890′s. I don’t think any conservative of sound mind believes this is possible, and I’m confident the overwhelming majority of conservatives wouldn’t see it as desirable, either. Whatever our issues with Progressivism and the New Deal, I don’t think any of us wants to return to an America of child labor and widespread poverty, not to mention deep-seated racism. We admire and subscribe to most of the principles that created the positive aspects of this society–the wealth, the dynamism, the freedom, the upward mobility–but we know there were problems that needed to be addressed, and we do not see the 1890′s as a paragon to which we must return.

Rather, we seek to apply the principles and sensibilities of Liberalism 3.0 to the modern world. We ask, what would the nation and liberalism look like today if they had not taken the dark turn toward statism represented by the New Deal? How would they have addressed the problems of racism, poverty, insecurity, and inequality without turning to quasi-fascistic big government solutions?

As an intellectual exercise, let’s ask how the remainder of the 20th Century would have been different if Calvin Coolidge had been re-elected in 1928 and had addressed the Panic of 1929 and the ensuing depression the same way President Harding addressed the panic and depression of 1920-21–that is, by letting markets bottom out and recover on their own, rather than with huge increases in taxes and tariffs and efforts to prevent wages from falling, as the progressive Hoover did. If the economy had recovered in 1931-32 as it did in 1922-23, there would have been no Great Depression and no New Deal. Which doesn’t mean we’d still have a 1920′s-style economy and society today, but that we would have addressed our problems from that point onward outside the framework of big government and New Deal statism.

So the question is not how can we turn the clock back to 1890, but how can we apply the principles and sensibilities of 3.0 liberalism (minus the racism) to the problems of today? And what would our society look like today if we had been doing that all along, instead of being diverted down the dark road of statism, which is inherently illiberal?

I believe answering those questions will lead us to the 5.0 Liberalism Professor Mead seeks.

Don’t forget low immigration from the 1920s to the 1960s.

FDR said “necessitous men are not free men” and introduced what he called a “second bill of rights.” His view of the good life was not about working. It was Epicurean–the good life is what one can have after one’s necessities are provided for. It is not about how one provides them. Hence he leads to the entitlement mentality.

With his focus on natural right, among other things, Lincoln would be more of a fouder-type liberal in this model, no?

If one rejects the philosophy of history here–history is about phases–what holds liberalism together? Is there an underlying definition of liberty in all these phases? I suspect that Wilson and other Progressives (including FDR who called his Commonwealth Club Address “On Progressive Government”) did not define it the same way as Jefferson and Lincoln. (And I take the Northern line here. Lincoln was a true heir of the founding. The Southerners always deny that, claiming he reformulated Jefferson’s ideas. The neo-confederates say that was a bad thing, since Wilson (a Southern boy) the have said it was a good thing.) In short, I am not sure that Progressivism was, in fact, liberal, but it might be that the founders’ constitution kept them from implementing their full program.

A book would be even more helpful in spreading the general awareness that a refocusing needs to take place in order that leaps can then be made. As a wise woman once told me ‘you cannot solve a problem until you have an awareness of it.’

The clear next step is to generate awareness of the true problem, the forest rather than the trees.

I hope a book is in the works.

Also, what about the TED conference? You should speak at it (so we can all watch it on youtube).

It is high time we had some really fresh and exciting re-viewing and re-visioning on government.

I’d surely like to see Silicon Valley intellectual buy-in to engagement with the problem you set before us, because I do think the next iteration of ordered liberty should resemble social networks.

Well, considering it was the white males who built the technology and the economy in the first place, that isn’t too surprising, is it?

2. “The blue model built big-box schools where the children of factory workers could get the standardized social and intellectual training necessary to enable most of them to graduate into the big-box Ford plant and shop in the big-box store. Maybe that was a huge social advance at one time, but is that something to aspire to or be proud of today?”

On average, the public schools in the 50s and 60s performed better then they do today — and they were far, far more cost effective.

3. “Voters simply will not be taxed to cover the costs of blue government, and in most cases they will vote out of office anyone who suggests otherwise.2”

You got that right, Brother.

1- Make education more congruent with the needs of contemporary society. Let’s bring back apprenticeships, specific certification, vocational training in high schools and the like. We need colleges, but too many people go to college these days and it costs them too much money for degrees that don’t prepare them for a career.

2- Let’s use technology to make government smaller, more efficient and more responsive to citizen’s needs.

3- Don’t forget social issues. Many social problems would be solved if people got married before having kids and stayed married after the kids come. Yes, yes, I know social mores are notoriously hard to change but that doesn’t mean we can’t try really, really hard. Churches, schools and government need to be onboard with this project.

I like WRM’s optimism and his making the point that change has to happen and we might as well get on with it. Write that book now, please!

What is an American with meager skills to do? The hope that all Americans can constantly be upskilled through education and training so that the best jobs would remain here is utopian. It is utopian and racist to believe that the majority of Americans are smarter, more motivated, more hardworking than the rest of the world. Furthermore, the rest of the world is not going to concede the high-technology ground to the US. The prattle about global division of labor and gains from trade that economists feed us, while not wholly wrong, is highly misleading. We may imagine a world where all Americans are rocket scientists, but no Chinese, Brazilian, Indian, is ever going to sign on to this plan. They want their own rocket scientists too. Thus the upskilling model is of limited utility. It will leave at least a third to a half of Americans behind. This is not to say that our education system needs no reform. It does, but that will not entirely solve the problem.

The second problem that the world is facing because of the rapid “rise of the rest,” is that human society is yet again heading for a Malthusian trap. The industrial revolution lulled us into believing that Malthus had been proved wrong, but if global warming is real, then perpetual economic growth becomes unthinkable. Humans have already faced two major Malthusian traps, each led to a revolution. The first to the neolithic revolution, the second to the industrial revolution. Each revolution led to a reduction in our personal autonomy in exchange for more stuff “in the aggregate.” The former produced authority, hierarchy and slavery; the latter transmuted slavery into wage slavery.

If global warming leads to yet another Malthusian trap, I think America is well placed to lead the next revolution as a way out of this trap. A return to “middle tech” yeomanry perhaps? A system where economic production once again moves back to households and small communities from global supply chains. There are enough technological trends out there that suggest that a return to middle tech yeomanry is not beyond the pale. Middle tech yeomanry could serve as a pretty good basis for Liberalism 5.0. Big government can help by removing legal hurdles to middle tech yeomanry, but ultimately if it occurs, it will occur through individual and local initiatives.

But honestly, Prof. Mead why leave the job of figuring out what Liberalism 5.0 might look like to poor souls like us?

Isn’t that why you get paid the big bucks?

Social Mores aren’t that impossible to change. Remember, the social mores of 200 years ago (Regency England) were not that different than the mores of today. (They also had access to prophylactic technology, which remains necessary to safely pursue those sorts of social mores.)

What came next?

The Victorian Era, and the greatest expansion of the British culture’s power over their environment and their neighbors that the world has ever seen.

Something to think about, whenever people try to convince you that the drugs-and-[anything goes] culture of today is “inevitable”… or “progress”.

http://www.city-journal.org/2012/bc0125kh.html

In the following notes want explore, as a practical ideal, the notion of factories in the countryside run on part-time jobs. By “in the countryside” I mean in areas out beyond the exurban fringe of our existing metropolitan areas. And by “run on part-time jobs” I mean that most of the people working in these factories – those doing routine wage-work — would be employed 18-to-24 hours per week.

Now whether such factories would be profitable is, of course, an interesting question. In many ways it is the most interesting question, since on the answer everything else must ultimately depend. But for the moment at least what interests me more — and what should interest my readers — are not the factories themselves so much as the new kinds of towns that might develop around them, and the new lifestyle that would become possible for the men and women who reside in those towns.

The lifestyle itself is easy to imagine. Being employed only part-time outside the home, ordinary working people will have a lot more free time at their disposal than they do nowadays: time which they could use to construct their own houses, cultivate small gardens, cook and eat at home, and care for their own children instead of placing them in daycare to be cared for by strangers. In other words people could start doing a lot more things for themselves and each other – directly and with their own hands – which now they pay others to do for them. You could call it a compromise — or better yet, a trade-off — between the age-old longing for the simple life and the economic imperatives of a modern industrial society.

But whatever you choose to call it I would like to take a few moments to sketch what I think are some of its natural advantages: ways it would enable ordinary people to make a more efficient use of their limited time and resources to satisfy their needs and desires. These are the “soft paths” to which my title refers.

ii.

First and most obvious of course are the advantages to the individual. She (or he) will have much more personal freedom than has traditionally been the case along with an enlargement in the scope and variety of activities that compose a working day. Instead of being bound to the daily routine of a nine-to-five job repeating the same set of actions week in and week out she will find herself spending half her working life as her own person, leading a far more varied and independent existence than is possible today: an existence much closer in spirit to the one in which we evolved as a species, and to which, I presume, we are adapted by nature. *

I’ve often wondered whether it was to something like this that scripture refers, where it is written:

“Thou hast left thy first love; remember, therefore, from whence thou art fallen?”

And is it really just a coincidence that those areas of our modern economy which have most stubbornly resisted the techniques of mass-production or else have yielded to them with inferior results – the building of our homes, the preparation of our food, and the care of our children — are also the areas of activity that offer us the greatest intrinsic rewards: which afford us opportunities to satisfy our instincts for workmanship, to express ourselves with the works of our hands, and to exercise our manifold capacities for reciprocity and affection?

I do not know the answer to these questions. But I do know that the new way of life I am proposing is one that will make the pursuit of happiness a far more agreeable enterprise than it is for most Americans nowadays, and one with better prospects of success.

iii.

Let me turn next to the family, which not only is oldest and most universal of all human institutions but also the one primarily responsible for the transmission of our culture and civilization. What effects would this new lifestyle have on the family?

To begin again with the obvious it is clear that parents would start spending a lot more time with their children and each other than is possible today, and that they would be doing something besides watching TV while plunked on the couch. Home and hearth would become again what until recently they always have been: scenes of domestic activity where every family member has useful roles to play and real responsibilities to meet. There certainly will be no shortage of quality time in the sense of opportunities for parents to interact with their children: to talk, joke, and play around with the as they share in the daily chores of life, or engage in more serious conversations whenever the occasion seems appropriate. Thus would the human family to be restored not only as a functioning economic institution but in its age-old role of nurture and support.

iv.

Something similar can be predicted for the institution of marriage, which not only is the biological basis of the family but also the foundation of its stability. The bonds of matrimony will certainly grow stronger once the earnings from two part-time jobs together with the contributions of two adult sets of hands are required to support an independent household.

Contrast this to the typical situation today where we find that both parents are employed full-time outside the home and can thus afford to live by themselves if they are so moved. Small wonder so many marriages now end in divorce! But under the terms of the new household economy I am proposing walking out of a marriage becomes a much less convenient option than it is now — which means that fewer couples are likely to go through the traumas of divorce, with all this implies for the happiness and emotional security of their children, to say nothing of themselves.

v.

We should also consider the possibility of a return to a more traditional, three-generation form of the family — not under one roof necessarily, but perhaps under two, at opposite ends of the garden. The advantages are manifold. For one thing grandparents, once they live close by, will be in a position to help look after their grandchildren – during the period they are still infants and toddlers especially — on those occasions that inevitable arise when both parents need to be away from home at the same time. And by the same token, later on in life when the grandparents themselves have grown old and are no longer able to live by themselves, their children and grandchildren will be in a position to help look after them.

As an alternative to daycare and nursing homes alone this old arrangement deserves our consideration. For not only does it offer a more natural and humane way to deal with these age-old problems of care, but one that is infinitely more affordable as well, at least for most working-class families.

vi.

Let us now turn to the issue of retirement. We have all read those stories in the newspaper about how Social Security is going to go broke and may not be there for the next generation. The aging of the baby-boom generation, as we all know by now, means that the ratio of people who are drawing money out of the Social Security system is growing to fall in relation to the number of people who are paying money in, a trend that seems destined to continue. What this portends, the experts keep telling us, is one of three things: either a reduction in Social Security benefits, a rise in the future age of retirement, or an increase in taxes on future workers’ wages. None of these is an attractive alternatives politically speaking, to say the very least.

But under the arrangement I am proposing this dilemma largely disappears. Once work and leisure are integrated into the fabric of everyday life, people will no longer feel the same need to retire the do todayy. Instead they can gravitate towards easier kinds of work as they grow older and towards an even shorter workweek: 12 hours behind a check-out counter, for example, instead of 18-to-24 hours on the assembly line. And when they eventually do reach a point in life when they are no longer able work at all, they will not have to rely on their monthly Social Security checks alone to meet all their material needs, as we have already seen. This means that their monthly benefits could be lower without compromising the quality of their lives.

And finally, at the very end of life, when death finally approaches as it inevitably does, instead of being carried off to a nursing home somewhere at enormous public expense the dying person can stay at home, where hospice services can be provided at a fraction of the cost, in which specially trained nurses would come to the house for an hour or two each day to assist the family with the physical and medical care of the patient. How much better to die that way, at home in one’s bed, surrounded by the voices of loved ones, than all alone in a hospital room or in a warehouse of strangers?

vii.

Let us turn next to the local neighborhood community, which, after the family, is the second oldest of all human institution, corresponding as it does to the primitive band and to the ancient and medieval village. What new sorts of neighborhoods might become possible, and how might they differ from the ones most of us grew up in?

One thing is for sure. We are going to see many more adults up and about during the regular course of the day. With half their working lives centered around the home grown-ups are bound to be round on a regular basis, tending their gardens, doing routine choirs around the house, or engaged in some other useful pursuit – whether something as simple as painting a porch swing or mending an appliance, or some- thing as complex as a major home improvement project. But what- ever they might happen to be doing the point is that these new neighborhoods of the future will no longer be the “deserted villages” most of us know, in which adults typically get up in the morning, climb into their automobiles, and drive away to work until the end of the day.

For the children this will have certain obvious advantages. They will be exposed to the adult world of work to a much greater extent than is possible in today’s society, where most real work is done away from home and out of sight of the children. Being the naturally curious creatures they are, children in the neighborhood will inevitably be drawn into the world of work: at first by looking, then later by asking, and finally by helping — and thus in the natural course of growing up will acquire a certain amount practical knowledge and a number useful skills, things which nowadays completely pass them by.

Another obvious advantage is that the same adults who are out working in their yards will be well-positioned to keep a collective eye out on the children in the neighborhood as they run and play among the houses, warning them away from danger and keeping them out of mischief, thus providing a useful extension to the family itself. Friendly faces in friendly places, it is easy to predict, will make the neighborhood a safer and more congenial place in which to work or play.

viii.

Nor should we overlook the many other possibilities for sharing. With so many adults at home during the day it becomes a simple matter of convenience to go next door to borrow a cup of sugar or to ask for a helping hand from the neighbor down the street. Visiting and casual hospitality are sure to be more common occurrences once one’s friends and neighbors begin to avail themselves of some of their new-found leisure.

Or consider such a simple thing as a neighborhood post office instead of individual mailboxes in front of each house. Not only would this save the postal service a good deal of time and expense but it would provide a convenient spot where neighbors are likely to run into one another, exchange gossip, and pass along any news that might be of local interest.

Neighbors might even elect to go in together to purchase a small neighborhood tractor which that they could all share in the spring to turn over their gardens. Or they might organize house-raising parties in the old Mid-Western barn-raising tradition: a useful as well as a very pleasant way to get through some of the earlier and heavier phases of construction. And, of course, there is the possibility of picnics on the 4th of July, a sure way to create a sense of local feeling and neighborhood solidarity.

ix.

Let me now say a few words on the subject of neighborhood planning. What would be the best way to arrange the houses in as neighborhood if we intend to take maximum advantage of the new possibilities for sharing?

Here I think we have something to learn from the Traditional Neighborhood Movement, as it is sometimes referred to, which is already underway in a number of places in the United States. One opportunity, in particular, stands out: a chance to get away from the contemporary practice of arranging our houses along both sides of the street like so many beads on a string. The alternative is to arrange them around a central open space — a village green — which would serve both as a neighborhood park and a playground for kids (see Figure 1).

Plan for a Hamlet from The Art of Building a Home, 1901. This was the earliest suggestion of grouping various combinations of houses and a break in the building line. It was intended to give a unified impression from the standpoint of a traditional village green, which was supposed to serve the same communal gathering purpose out-of-doors that the two story living room did for the family inside. The thought was to draw people to a place so that favorable and positive things might begin to happen to them.

As you can see from the figure a second habit we might get out of is that of placing our houses back from the street with large lawns in front. Instead we could arrange our houses close to the street, facing the park, and give them front porches, as was commonly the practice in most towns in America before the age of the automobile. This arrangement would make for easy line-of-sight communication between the house and the park, and between the porch and any pedestrians who might happen to be walking by on the sidewalk that runs in front of each house.

Of course if the houses are set forward like this it means that the gardens will have to be located behind, in the long back yards that would stretch from the rear of each house, with the grandparents’ quarters being located at the far end of the garden, but accessible by a small alleyway that runs across the back of each lot. The advantage of this arrangement is that it would define a space — bounded by the larger house in front and the smaller one behind — of relative peace and quiet: a place not open to the street, where a person could sit and meditate, or think, or sing the baby to sleep, and not be bothered (see Figure 2).

“It has been computed by some Political Arithmetician, that if every Man and Woman would work four Hours each Day on something useful, that Labour would produce sufficient to procure all the Necessaries and Comforts of Life, Want and Misery would be banished out of the World, and the rest of the 24 Hours might be Leisure and Pleasure. What occasions then so much Want and Misery?”

Benjamin Franklin

Sign in | Recent Site Activity | Terms | Report Abuse | Print page | Powered by Google Sites