For families of victims of juvenile murderers, ruling reopens 'traumatic wounds'

Family photo/Courtesy of Bobbi Jamriska

Kristina Grill, 15, was murdered in 1993 by her ex-boyfriend, who was also 15 at the time of her death and 16 when he was convicted. She's seen in this file photo in Pennsylvania a year before her murder.

Nineteen years ago, Bobbi Jamriska's younger sister was found murdered in a Pennsylvania schoolyard. As Jamriska grieved, one thing brought her solace: When a court found her sister's 16-year-old ex-boyfriend guilty and sentenced him to life in prison without parole.

"When you get up every day, you think about what happened, but at least you know that there was that one constant, that life-without-parole was going to make sure that you never had to relive that part of it," said Jamriska, 40, who lives in Pittsburgh.

But three months ago, the Supreme Court struck down mandatory life-without-parole sentences for juveniles as cruel and unusual punishment. While the June 25 ruling wasn't necessarily designed to be applied retroactively, some youth advocates are trying to use it to free so-called "juvenile lifers," setting off a series of battles over what to do with the approximately 2,100 convicted murderers who were handed mandatory life-without-parole sentences for acts committed as youths.

"After the [Supreme Court] ruling, everyone felt like they were reliving the trial phase and their loved ones' murder," said Jamriska, who traveled to Washington, D.C., with other victims' families to protest the ruling.For victims' families, the decision has had huge emotional, and in some cases, legal implications.

"There were a lot of families who didn't have any idea that this was even possible," she said. "For them, it was literally one day business as usual, and then the next day, on the news, their whole world got turned upside down."She is part of a support group called the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers.

Pennsylvania, where Jamriska lives, has the biggest concentration of juveniles serving mandatory life sentences -- about 480 of them, the oldest of whom was convicted almost 60 years ago and is now in his 70s, according to the Juvenile Law Center. Earlier this month, the state Supreme Court in Pennsylvania began hearing arguments for why some of the lifers there should be paroled, including the ex-boyfriend who killed Jamriska's sister in 1993.

No one in the legal system told Jamriska that the parole arguments involved her sister's killer. She found out from a reporter's voicemail about three weeks after the Supreme Court ruling that lawyers were trying to get parole for him.

Jamriska was stunned, but she said a lack of communication is somewhat understandable.

Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins / teenkillers.org

Bobbi Jamriska, of Pennsylvania, right, and Jody Robinson, left, of Michigan, another member of the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers, are seen advocating for victims' families' rights on March 20, 2012, outside of the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., as the Supreme Court heard arguments on whether mandatory life without parole was cruel and unusual punishment for convicted juvenile murderers.

"There never was a contingency for if this person who was sent to life in prison with no parole is suddenly able to get out," she said. "The DA's office isn't really staffed to manage that influx of appeals and those victims who are trying to get information -- I don't blame them."

The state Supreme Court has put the arguments on hold and didn't give a timeline for a ruling. The Pennsylvania legislature still needs to come up with an appropriate alternative punishment for minors going forward.

"The sentencing scheme in Pennsylvania currently provides that for any individual, juvenile or adult, convicted of first or second-degree homicide must either receive a sentence of death or a sentence of life without parole. For juveniles, that mandatory sentence of life without parole has been declared unconstitutional," Marsha Levick, deputy director and chief counsel at the Juvenile Law Center, said. "We think the courts should look to the next most severe sentence that is statutorily available in the state. Here, that means a sentence for third-degree murder, where you have a maximum sentence of 40 years."

Levick suspects lawyers in other states will argue for that too. Since the Supreme Court ruling, North Carolina has passed a law replacing the mandatory life without prison sentence with a 25 years to life sentence; California's governor is currently evaluating a law that sets up two different schemes where parole eligibility comes in at either 15 or 25 years to life, Levick said. In all, 28 states still allow mandatory life-without-parole sentences for minors, a situation that will have to change.

"States can still impose life without parole," she said. "They just can't make it the only sentence available."

As some juvenile advocates try to undo sentences that have already been imposed, Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins, 54, president of the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers, worries about the families of their victims.

"Whenever you reopen traumatic wounds or you're triggering a retraumatization, you're talking about something that is going to affect people's work, their sleep, their health, their marriages -- everything," she said.

Victims can only rely on each other for support, Jenkins said.

"They don't register for victim notification and they don't monitor what's happening, and then you get these reactions like what we've been getting in our organization," Bishop-Jenkins said. "We've been trying very hard to find people to let them know that this multi-billion dollar campaign to free their loved ones' killers is going on and they're just shocked."

Family photo/Courtesy of Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins

From left to right: Richard Langert and Nancy Bishop Langert are seen on their wedding day in 1987 in Kenilworth, Ill., with Nancy's parents and sister, Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins, far right. The Langerts were murdered by a 16-year-old in 1990.

There are potential legal issues too: Bishop-Jenkins' pregnant sister and brother-in-law were murdered in their home in Winnetka, Ill., 22 years ago. It was Bishop-Jenkins' father who found their bodies; his testimony served as crucial evidence in the initial trial. Eight years ago, her father died of cancer. She says the judge from the first trial has also died.

She now fears she and her mom, 83, could have to face her sister's killer in sentencing hearings in court. And while she doubts he will be granted parole, she said she worries lawyers may try again every couple of years."My father was the best eyewitness to the carnage of the crime scene. We didn't videotape him talking about the crime," Bishop-Jenkins said. "We didn't get the transcript of what the judge said at the sentencing hearing where he gave this speech about if anybody deserved life without parole, he did."

SECTION I: CRIME & PUNISHMENT IN THE U.S.

JUVENILES & THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM

- Percent of juveniles taken into police custody, handled within department and released, 1971: 45.0%

- Percent of juveniles taken into police custody, handled within department and released, 1999: 22.5%

- Percent of juveniles taken into police custody and referred to criminal or adult court, 1971: 1.3%

- Percent of juveniles taken into police custody and referred to criminal or adult court, 1999: 6.4%

- Number of states where defendants aged 16 or older are automatically handled by the adult criminal system: 3

- Number of states where defendants aged 17 or older are automatically handled by the adult criminal system: 10

- Number of states that allow at least some defendants under 18 to be handled by the adult criminal system: 50

- Number of persons under 18 held in State adult prisons, 1997: 5,400

- Number of persons under 18 held in local jails, 1997: 9,100

- Number of persons under 18 held in juvenile facilities, 1997: 86,010

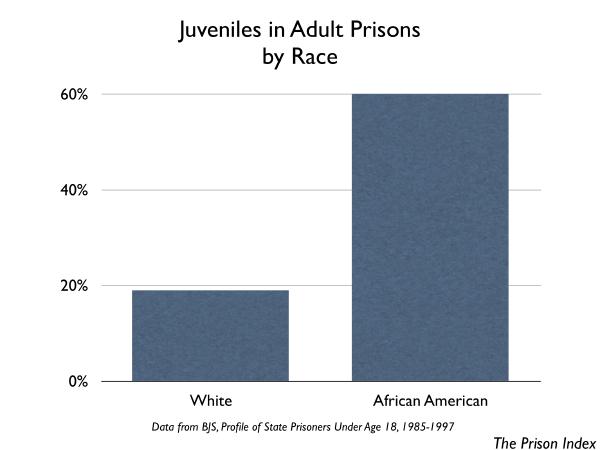

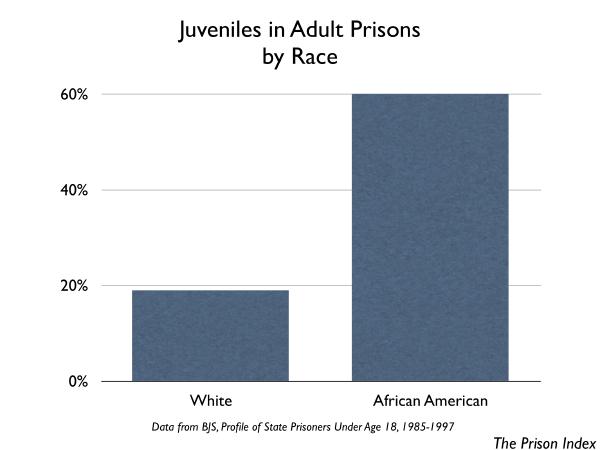

- Percent of state prisoners over 18 who are African-American: 46%

- Percent of state prisoners under 18 who are African-American: 60%

- Mean sentence to be served by persons under 18 sentenced to a state prison, in months: 44-82

- Percent of released prisoners who were sentenced to an adult prison before they were 18 who are released without a 9th grade education: 26%

- Percent of released prisoners who were sentenced to an adult prison before they were 18 who are later released without a high school diploma or GED: 90%

This page is an excerpt from The Prison Index: Taking the Pulse of the Crime Control Industry (2003) by Peter Wagner, published by the Western Prison Project and the Prison Policy Initiative..

No comments:

Post a Comment