Auction 2012 is a weeklong series in collaboration with "The Dylan Ratigan Show" and United Republic.

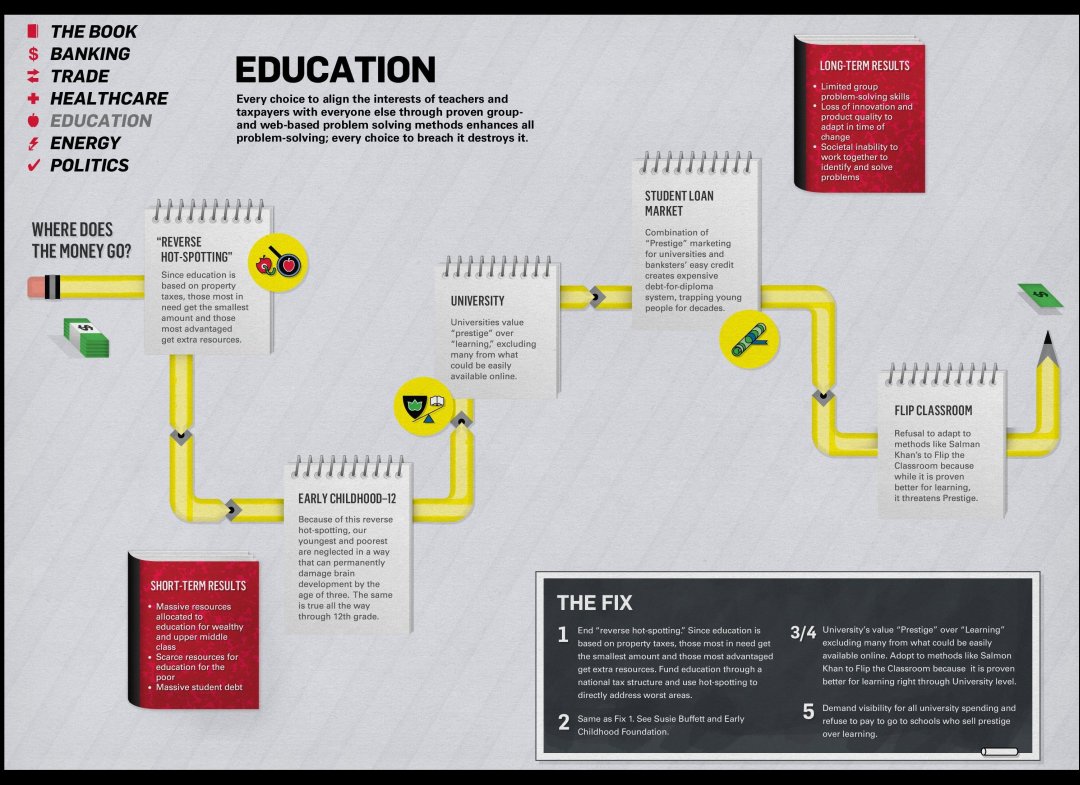

As the Great Recession propelled millions into the ranks of the unemployed more than three years ago, one industry in particular saw a surge in new business: for-profit higher education.

Enrollments and revenues skyrocketed at publicly traded corporations such as Education Management Corp. and Bridgepoint Education, which aggressively promoted degree programs said to offer crucial job training. The swift growth captured the attention of the Obama administration: Data showed that for-profit colleges accounted for nearly half of the defaults on federal student loans, despite educating only about 10 percent of the nation's college students.

Beginning in 2010, the administration announced a broad package of new regulations that would crack down on programs that leave students with outsized debt and few career prospects. But a year later, those rules had been substantially weakened, following a $13 million lobbying blitz by the colleges aided by some of Washington's most powerful Democratic influence peddlers.

"Big money won, and students lost," said Amy Wilkins, vice president of government affairs at the Education Trust, a student advocacy group. "The really eye-popping profits of the industry allowed them to plow huge money into lobbying against a strong regulation."

The well-coordinated lobbying and public relations campaign, targeted largely at Democrats, was an effort to protect the industry's access to more than $30 billion in federal student loans and grants that fuel the vast majority of its revenues. Some of the largest higher education corporations receive more than 85 percent of their revenue from federal student aid dollars.

Among the all-star cast of lobbyists hired by the industry: former Democratic House Majority Leader Dick Gephardt; Tony Podesta, one of the most prominent lobbyists in Washington and the brother of John Podesta, who led President Barack Obama's transition team; and Penny Lee, a former top adviser to Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) who was also a senior staff member for the Democratic National Committee. In total, 14 former members of Congress were hired by the industry to fight regulations that would have cut federal aid to programs in which students fared poorly.

During a hearing on for-profit colleges last year, Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa), chairman of the Senate education committee, called the lobbying effort "one of the most intense I've seen in my 32 years here, which tells me that there's a lot of money at stake."

The proposed "gainful employment" regulation aimed to gauge whether such schools were overpromising and under-delivering to students. Specifically, the rules were meant to measure student outcomes in two ways: whether students repay at least a portion of their student loans and whether graduates have excessive debt burdens compared to their income after college.

In order for a program to be disqualified from receiving federal student aid dollars, more than 65 percent of students would have to be delinquent in repaying their loans, and graduates would have loan debts that constituted more than 30 percent of their discretionary income or more than 12 percent of their total earnings.

Many student advocacy groups argued that educational programs should be held accountable if their students weren't prepared for careers that would allow them to pay off their debts. But the for-profit college industry turned that message on its head, contending that the regulations would unfairly harm students.

"It does literally threaten the existence of hundreds, if not thousands, of programs and threaten the ability of hundreds of thousands of students to continue to get an education," said Harris Miller, past president of the Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities, an industry trade group, in an interview with The Huffington Post last year.

On top of the millions spent on lobbying against the proposed rules, for-profit colleges boosted campaign donations to Congress, directing two-thirds of their total donations during the 2010 election cycle toward Democrats, according to an analysis by Huffington Post.

And months before the administration released the gainful-employment regulations, the House of Representatives attempted to pre-empt them. In a February 2011 vote, the House decided by an overwhelming margin to approve a budget amendment that would have blocked the Department of Education from moving forward with the rules.

Though the vote was largely symbolic, it revealed many Democrats siding with the for-profit colleges, including House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) and Democratic National Committee Chairwoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz. (D-Fla.).

"One of the most unseemly things was how many people who considered themselves progressives -- who worked for the Obama administration, who acted as champions of upward mobility in America and for low-income people and people of color -- readily accepted money to lobby for a position that was harmful to all those interests," said David Halperin, a former senior vice president at the Center for American Progress who is now a senior fellow at United Republic, an organization that aims to counter the influence of money in politics.

In the months after, industry representatives continued to meet with top policy officials in the Obama administration, according to meeting records from the Office of Management and Budget. Last May, the month before the final regulations were released, the White House had 17 separate meetings with for-profit college representatives.

Among those in attendance were influential executives such as Donald Graham, chairman and chief executive of the Washington Post Co., which owns Kaplan University; and John "Jock" McKernan, chairman of Education Management Corp., a former congressman and Maine governor, and husband of Sen. Olympia Snowe (R-Maine). By contrast, a coalition of civil rights and student advocacy groups met just once with the administration.

When the regulations were finalized in June, the package had been diluted significantly compared to an initial draft released a year earlier. For-profit colleges were given a three-year grace period before facing serious sanctions on their intake of federal student loan dollars.

And instead of being judged based on one year of poor student outcomes, schools would have to fail every student debt category in three out of four years in order to be cut off from the vast pool of federal subsidies.

Although industry representatives still complained the regulations were too much, Wall Street sent a clear message the next day: Stocks surged for nearly every corporation owning for-profit colleges, with some of the largest companies seeing gains of more than 20 percent.

Nonetheless, the Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities sued the Obama administration in July, arguing the regulations must be blocked "in order to protect 3.8 million students who attend private sector colleges and universities today and those who will attend our schools in the future." A spokesman for another industry trade group, the Coalition for Educational Success, said this week that the group believes the rule "exceeds [the administration's] authority, is based on faulty data and economic theory, and will shut out the very students who have the most to gain from Title IV student aid."

Those who wanted more accountability from for-profit colleges have argued that the continued protest reveals the degree to which schools were under-serving students.

"The final rule only deals with the worst of the worst of these programs," said Pauline Abernathy, vice president of the Institute for College Access and Success. "Given that the standards are so modest, it suggests that these programs were actually worse than many people feared."

The Auction 2012 series explores the ways industries influence policymaking in five areas: banking, energy, health care, trade and education. Read Dylan Ratigan's blog post introducing the series and his blog post on education.

No comments:

Post a Comment